Performance Obligations

Framework for identification of performance obligations with an illustrative application for validators of proof-of-stake blockchain networks.

The process of identifying performance obligations often feels like a black box, where the output may seem disconnected from the input. It frequently appears that some goods and/or services have been omitted from the analysis, and without knowledge of the nuances of ASC 606, it can be challenging to understand why this is happening. To address this issue, I have created the following process to help ensure the complete identification and assessment of promised goods and services:

Sub-Step 1

List all specified promises (goods, services, and material rights) in the arrangement with a customer.

Sub-Step 2

Exclude any promises that fall within the scope of other accounting standard codification topics (e.g., leases).

Sub-Step 3

Exclude all administrative and setup tasks (activities that do not transfer value).

It is also good practice to identify any payments specifically designated for these administrative and setup tasks for further analysis.

Sub-Step 4

Exclude all promises that are immaterial at the contract level (so that it would not be appropriate to allocate any portion of the transaction price to them).

Identifying contractual payments specifically related to immaterial promises is also a good practice, as it provides useful information for the next step of the analysis.

Sub-Step 5

Exclude all promises that involve third parties where the reporting entity does not act as the principal, and include the related promises to arrange for such goods and/or services if such promise is present.

Sub-Step 6

Identify separate performance obligations for all promises that are distinct.

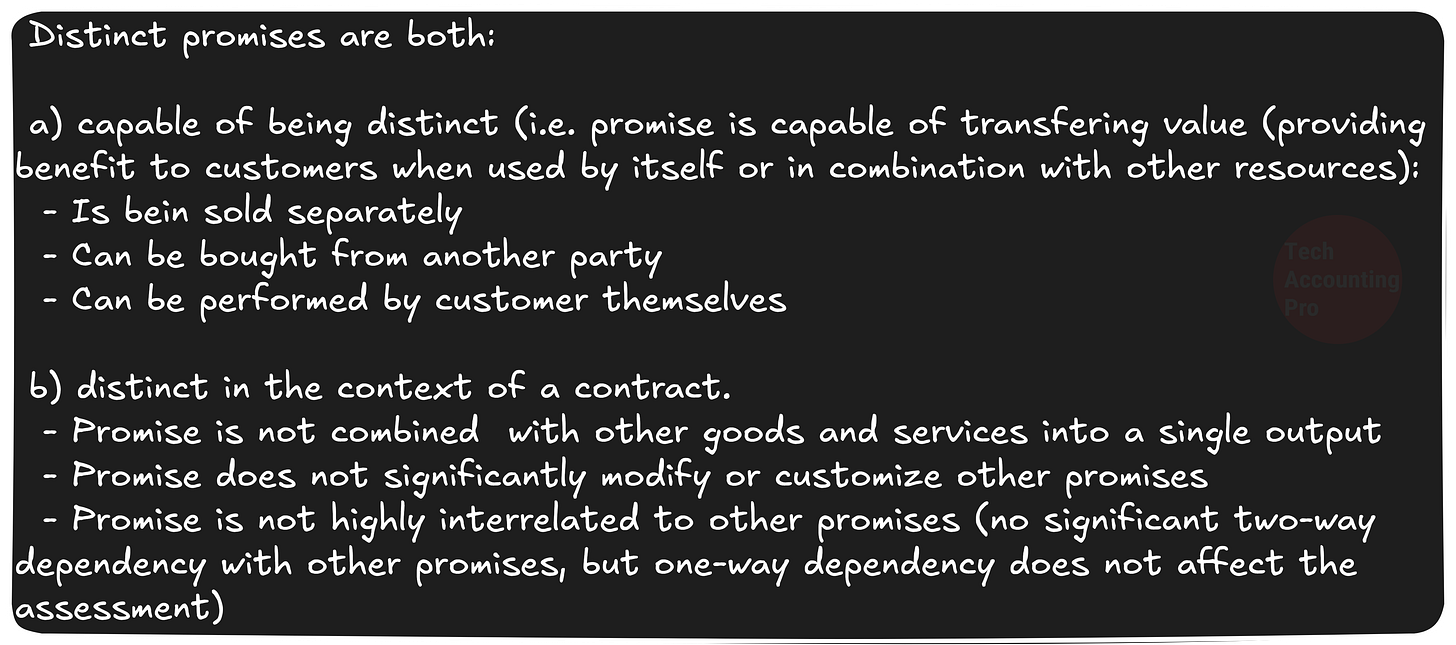

Now we need to evaluate whether identified promises are distinct. As per FASB ASC 606-10-25-19, a distinct performance obligation should meet both of the following criteria:

"The customer can benefit from the good or service either on its own or together with other resources that are readily available to the customer."

"The entity's promise to transfer the good or service to the customer is separately identifiable from other promises in the contract (that is, the promise to transfer the good or service is distinct within the context of the contract)."

This topic by itself requires a separate post to explore fully, but the overall approach is outlined below:

Sub-Step 7

Identify combined performance obligations for promises that are not distinct individually, but distinct when combined with other promises.

This step addresses situations where individual promises are not distinct because they are integrated into a single output, have high interdependency, or are significantly modified/customized. An example of this is construction, where individual materials or services are combined to create a unified output, such as a building.

Additional (Optional) Sub-Step 8

If non-distinct promises are significant within the context of a contract (e.g., due to the amount of consideration received), identify whether these relate to any single specified promise previously identified as a distinct performance obligation.

Evaluating the relationship between non-distinct and distinct services at this stage enhances consistency and helps reinforce allocation requirements related to the transaction price among performance obligations. This exercise prepares the foundation for future work required in Step #4 of the ASC 606 revenue recognition model.

Let’s apply this process to identify the performance obligations of validators.

Validators run servers that execute a blockchain's software binary and attract staking funding from delegators of digital assets. These assets serve as a guarantee of validators' trustworthiness and are used to penalize bad actors in the system. The amount of assets staked with each validator node determines the voting power of a private key that validators encode into cryptographic signatures. These signatures are used to broadcast votes for or against newly proposed blocks. To deliver these promises:

Sub-Step 1. Promised goods, services, and material rights:

A list of promises identified in typical arrangements between validators and their staking customers:

Validation of transactions

Proposing new blocks

Voting on proposed blocks

Provisioning voted blocks upon consensus

Voting on governance proposals

Historical data storage

Node uptime maintenance

Delivery of digital asset rewards

Periodic reporting for delegators

Technical support

Educational events and content

Typically, no material rights for future services are granted to delegators who enter into agreements with validators. This is because the number of transactions processed within each epoch varies based on the volume of activity of network participants. After each block is created, validators are still required to process a variable number of transactions for the remainder of an epoch.

Sub-Step 2. Promises in the scope of other topics

No such promises were identified.

Sub-Steps 3-6.

Each promised service can be evaluated using the format suggested below:

From this assessment, we see that none of the promises individually constitutes a separate performance obligation.

Note that validators are the primary responsible party for validation services and have full control over service performance. However, validators typically have neither control nor an obligation to transfer digital assets distributed as network awards in staking arrangements to delegators.

Sub-Step 7. Identify combined performance obligations

When combined, all of these promises represent a single performance obligation: to ensure that validator nodes run with maximum uptime in a manner reasonably intended to arrange for the generation of digital asset rewards for delegators.

Sub-Step 8.

Not applicable.

Conclusion.

Validators of proof-of-stake networks typically have a single performance obligation which is to validate network transactions.