Token Compensation Accounting

How should entities account for the token compensation plans under US GAAP?

I recently spoke with several technical accounting professionals about how they account for various forms of token compensation and was surprised by the diversity of approaches. Today, we will take a detailed look at the accounting for token compensation.

1. Definition

Let’s start by defining what token compensation is:

Token compensation is a benefit plan established by an entity in which employees receive project tokens or other tokens issued by the employer, or where the employer incurs liabilities to employees based on the price of these project tokens.

We will specifically exclude from our discussion any plans where tokens represent stock in the company’s equity or provide the employee with rights similar to those of equity holders. Accounting for these compensation plans is likely guided by stock-based compensation accounting rules, which is a separate and extensive topic that we cannot cover in a single blog post. Instead, we will focus on more traditional forms of token compensation plans.

Web3 companies often offer employees various token compensation plans, and these plans frequently have unique and unusual terms. Toku, a company specializing in the administration of token compensation, has published research showing that the three most common plans offered to employees of crypto-native companies are:

Restricted Token Awards (RTAs). These are grants of tokens in exchange for services, with the immediate transfer of tokens to the employee’s wallet or smart contract. These tokens come with programmatic restrictions on transfer and enforce vesting conditions (unvested tokens are subject to clawback in case of termination). These awards are typical for projects that have already minted tokens but have not yet initiated a public sale.

Token Purchase Agreements (TPAs). Employees purchase tokens at an agreed-upon below-market price. These agreements may also offer employees protection from downside market movement to avoid a situation where employees end up with a loss position that effectively reduces their compensation.

Restricted Token Units (RTUs). Similar to RTAs, but tokens are only transferred to employees at the vesting date, typically in quarterly tranches over a four-year vesting term with a one-year cliff. RTUs are common for projects that have already publicly launched tokens.

2. Accounting

2.1. Expense Recognition

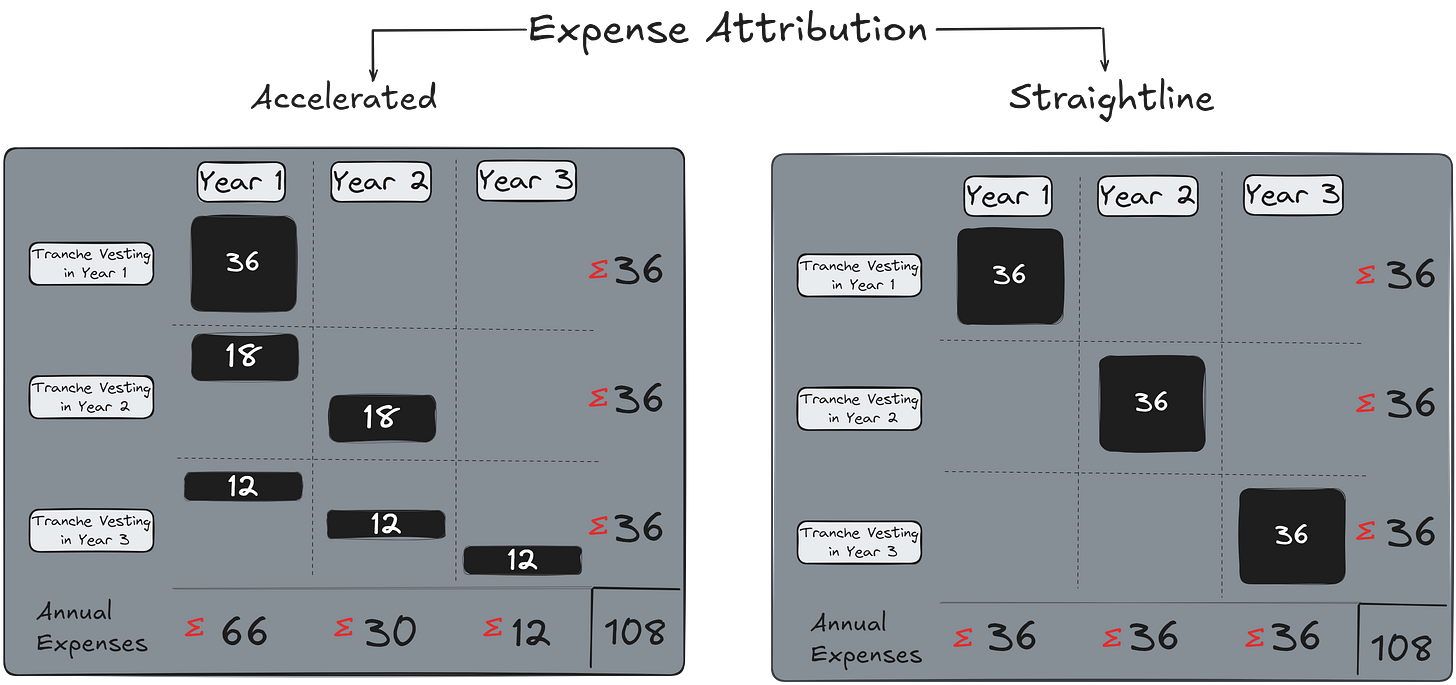

Entities account for token compensation plans by recognizing the anticipated payout over the service period in a systematic and rational manner as per [ASC 710-10-25-9]. This systematic approach is generally implemented via one of two methods:

Accelerated expense attribution

Straight-line expense attribution

Both methods recognize expenses over the vesting period as illustrated below:

Generally, labor costs should be recognized over the period of requisite service, with the full amount of expense recognized at the earliest of when the expense (or its portion) [FASB ASC 710-10-20, -30]:

Has been earned and

Becomes unforfeitable

In practice, this means that the amounts calculated using either expense attribution method need to be compared to the total value of vested tokens as of each reporting date. When the value of vested tokens exceeds the recognized expense, an additional catch-up expense should be recorded in the month of the variance.

2.2. Measurement

Classification of the token grant obligation. Because project tokens within the scope of this post do not provide interest in the entity’s residual assets, token grant obligations are treated as a company liability rather than a component of equity.

However, it is useful to consider the guidance on accounting for stock-based compensation costs arising from liability-classified awards. Under US GAAP, these awards are measured each reporting period, and changes in fair value are recorded as compensation expenses. However, the accounting model for liability-classified stock awards is actually the model for financial liability-classified stock awards. In contrast, token awards result in token grant liabilities that may be financial or non-financial liabilities depending on the terms of the specific plan. If the token grant liability is a financial liability, we could follow the guidance for liability-classified stock-based compensation as an analogy. However, the accounting for non-financial token grant liabilities has distinct features:

Host contract liability is measured using inception date token prices

Embedded derivative asset/liability is used to track changes in the fiat value of the token grant liability due to changes in token prices. Embedded derivative assets/liabilities are presented separately from the token grant liability [1]

Unrealized remeasurement gain/(loss) on embedded derivatives accounts for changes in the valuation of token grant liability resulting from changes in token prices. This gain/(loss) may be presented as part of the compensation expense or separately in another caption of the operating results section in the P&L.

Token compensation expense should initially be recorded as:

DEBIT Compensation Expense

CREDIT Token Grant Liability

Subsequently, the pro-rata vested portion of the token grant liability is remeasured each reporting date and recorded as a liability with a corresponding compensation expense. In other words, token grants should be expensed on a tranche-by-tranche basis over the vesting term of each tranche, and each tranche is remeasured based on active market price. This results in front-loaded expense recognition.

Performance and market conditions. Token compensation plans may contain performance or market conditions. Accounting for these conditions follows the guidance of ASC 710. Entities should accrue compensation costs over the requisite period of employees’ service, if they believe that (it is probable that) performance conditions will be satisfied. When the performance condition is assessed as not probable, no cost is recorded, and any previously recorded cost is reversed. When management changes its assessment and believes the performance condition is probable, the adjustment to compensation costs may be recorded using either the cumulative catch-up or prospective method:

Cumulative catch-up method:

Recognize separately as catchup adjustments the probable estimated compensation expense that would accrue if the condition was originally estimated as probable. Record such adjustments in the period of assessment change.

Recognize the remaining probable estimated compensation expense over the period when future service is rendered.

Prospective method:

Recognize the total probable estimated compensation expense over the remaining period prospectively.

Forfeitures. As mentioned earlier, unvested tokens of terminated employees are often subject to clawback, meaning they are forfeited at the termination date. Similar to cash compensation plans, there is no specific guidance on accounting for forfeitures in token compensation plans. By analogy with ASC 718, management may choose to estimate future forfeitures. However, entities using token compensation plans typically lack sufficient historical data to form a reasonable estimate of such forfeitures, as these entities are often startups. As a result, the best practice is to record actual forfeitures of benefits under token compensation plans as they occur.

2.3. Settlement

Several factors are important to consider when the token grant liability is being settled:

Reclassify cumulative remeasurement gain/(loss) from unrealized to realized.

Recognize the settlement gain that effectively offsets all historical token compensation expenses. This results from the fact that the token grant liability is settled by payments of tokens issued by the company, which have zero book value.

Derecognize embedded derivative/assets (if any) related to the settled token grant obligation.

Tax withholding obligations should be accounted for as appropriate for the type of grant being settled.

A sample journal entry is presented below:

DEBIT Token Grant Liability

DEBIT Embedded Derivative Liability

CREDIT Embedded Derivative Assets

CREDIT Digital Assets

CREDIT Realized Gain on Disposal of Tokens

DEBIT Realized Loss on Disposal of Tokens

CREDIT Tax Withholding Obligations

2.4. Modification Accounting

As mentioned earlier, token grant liabilities may include both financial and non-financial liabilities depending on the plan terms.

For financial token grant liabilities it makes sense to adopt the modification accounting model from liability-classified stock-based compensation:

“The general principle of exchanging the original award for a new award also applies to a modification of a liability-classified award. Unlike an equity-classified award, however, a liability-classified award is remeasured at fair value at the end of each reporting period. Therefore, a company simply recognizes the fair value of the modified award by using the modified terms at the modification date. There is no “floor” or requirement to recognize at least as much as the grant-date fair value of a liability classified award; the total compensation expense will equal the fair value on the settlement date.”

Currently, no explicit guidance exists on the accounting for modifications of non-financial token grants. Further, available analogies are not fully applicable. We generally believe that the “floor” requirements to recognize token compensation expense may apply to modifications of token grants accounted for as non-financial liabilities, but there is no authoritative reference to help determine whether this accounting treatment is appropriate.

3. Examples

Let’s examine some illustrative examples of how the guidance we’ve discussed applies to different types of token compensation plans, including those we identified at the beginning of this post and some additional types discussed below.

Illustration 1 - Restricted Token Agreements

Because the employer may maintain effective control over unvested tokens stored in separate accounts, we should evaluate:

Whether tokens should be recorded on the employer’s books before vesting.

How the employer should recognize and present the values of token grant liability for tokens recognized on the employer’s balance sheet.

In most cases, accounting should follow the analogy with the accounting for deferred compensation plans with assets held in a Rabbi Trust. Based on this approach:

Unvested tokens are recorded on the company’s books as assets (although these assets will likely have no book value).

Token grant liabilities are recorded separately and on a gross basis. Token grant liabilities are derecognized as tokens vest and become unrestricted.

Illustration 2 - Token Purchase Agreements

The discount to fair value should be recorded as a compensation expense.

Illustration 3 - Restricted Token Units

Record expenses based on the fair value of each vested tranche as they are transferred to employees.

Illustration 4 - Impact of Different Types of Vesting Schedules

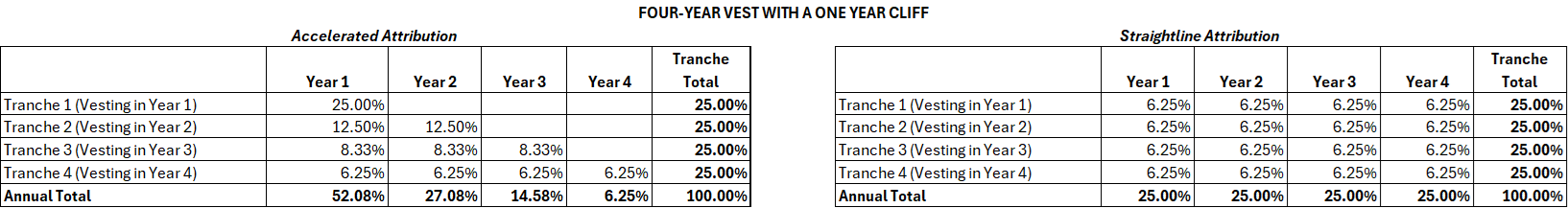

The Token Compensation Guide by a16z identifies three types of token vesting schedules most commonly used by crypto startups:

Four-year vest with a one-year cliff

“In this model, employees get a batch of tokens when they’re hired. The first quarter of the grant vests after the first year, and a percentage of the remaining tokens vest each month (or quarter or year, etc).”

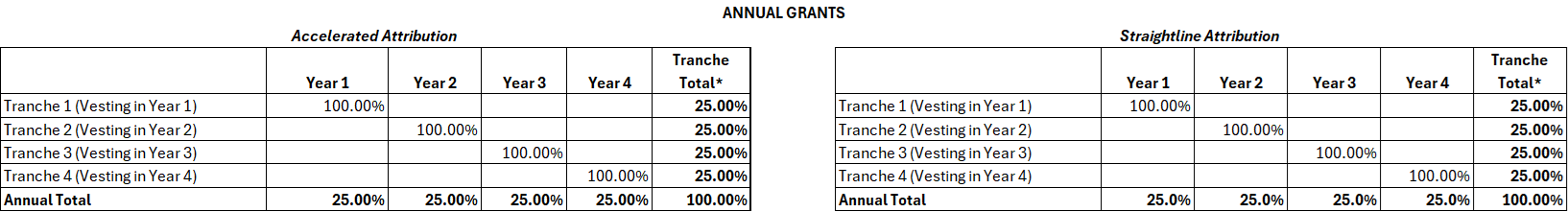

Annual grants

“Given how much token prices change over time, some teams find that it doesn’t make sense to grant tokens over multiple-year periods. This model therefore favors offering awards on a yearly basis. Each employee would get an annual market-rate token grant. Then, after the first grant, talent teams typically add performance metrics to the calculation.”

*Percentages shown for annual grants may be a little bit confusing. Let me explain. We wanted to illustrate the portion of total compensation expense recognized during each of the four years of the vesting schedule. However, for annual grants, the full amount (or 100%) is vested each single year. From the perspective of the four-year time horizon, the same amount comprises 25% of the total token compensation costs (assuming all other variables remain the same in each period, which is clearly an unrealistic assumption).

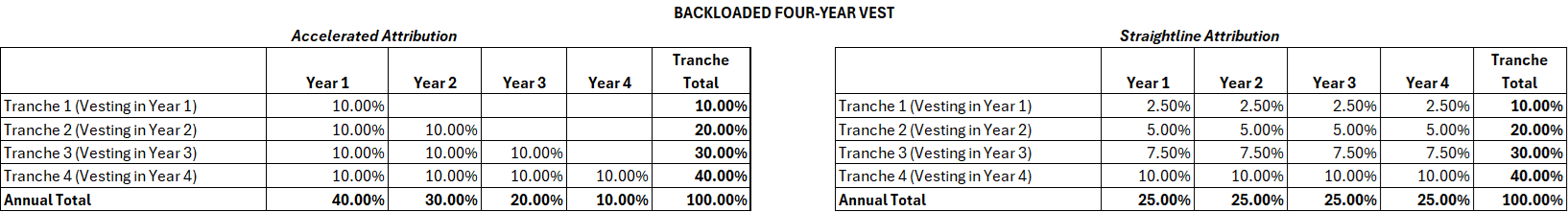

Backloaded four-year vest

“This model is designed to keep employee engagement high — by increasing the size of the vest over time, starting with a smaller percentage (say, 10%), and working up to 100% vested at the end of four years. This model also often involves a 1-year cliff – very few companies would offer tokens that vest without a cliff.”

Conclusion

Understanding the nuances of accounting for token compensation is crucial for accountants in web3. As token compensation plans continue to evolve, accounting professionals need to stay informed about best practices and emerging guidance to ensure accurate and compliant financial reporting.

Footnotes

[1] Reporting entities may elect the fair value measurement option to revalue the liability denominated in assets readily convertible to cash as of each reporting date based on updated token fair values.